aesterion

winter 2026

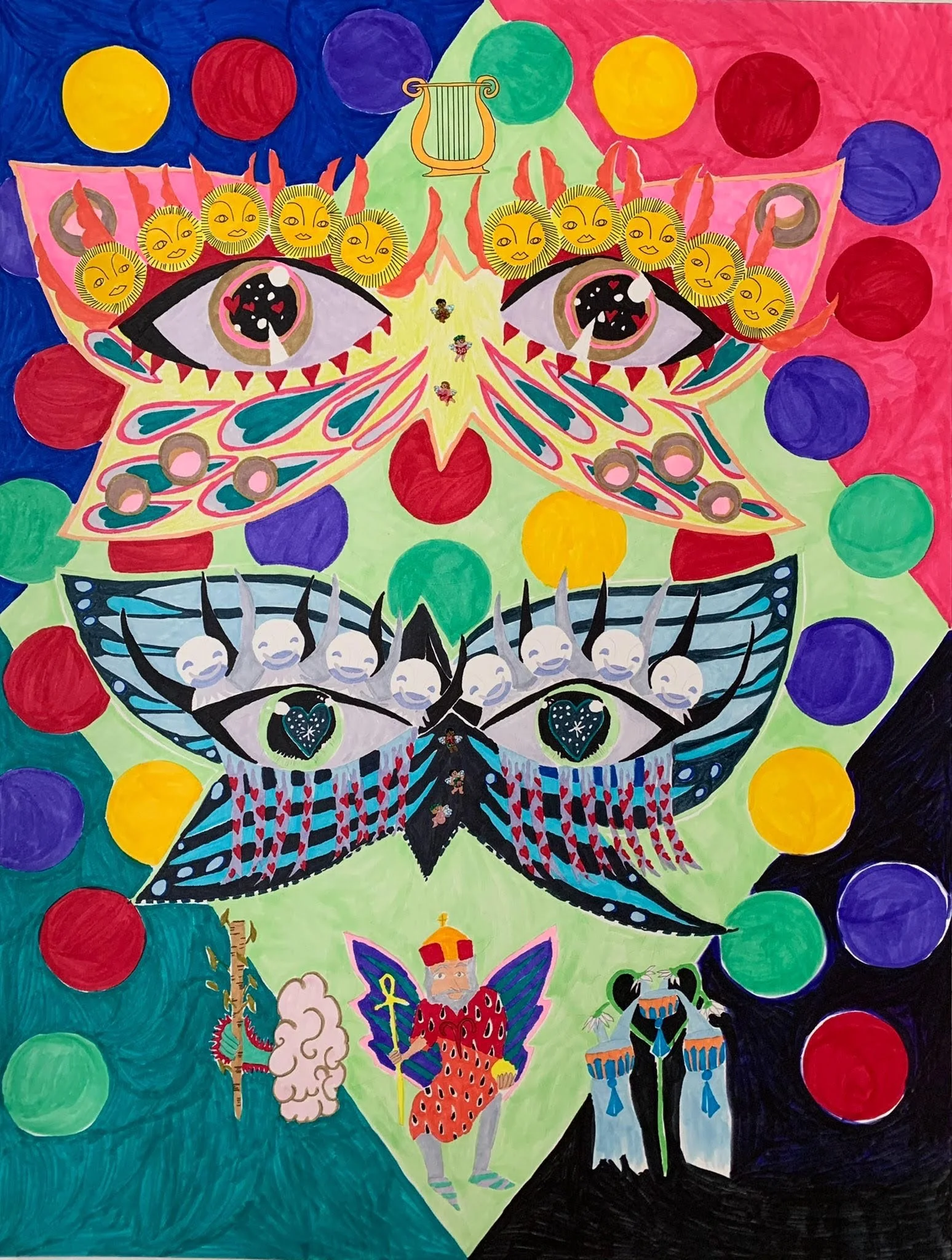

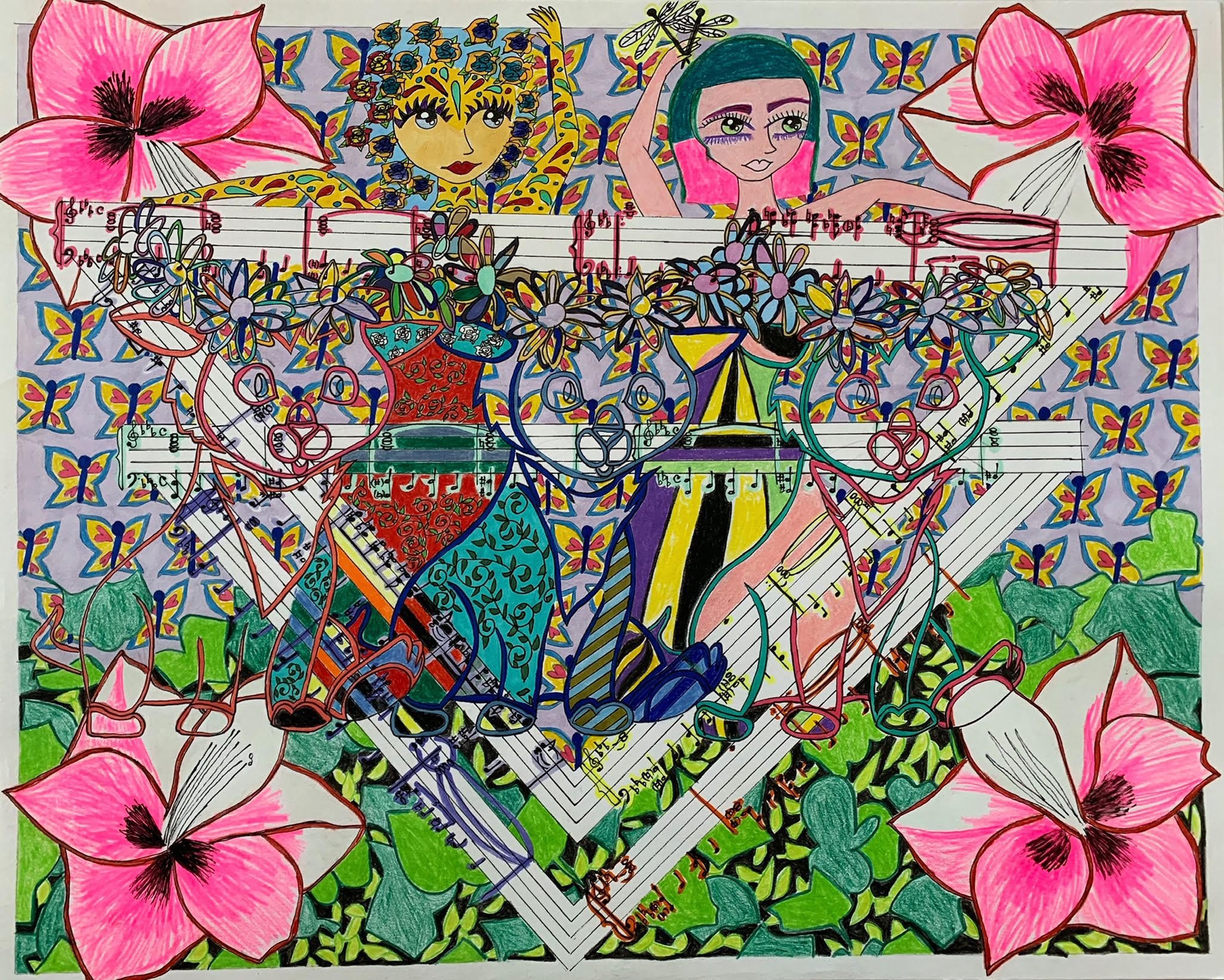

Sun and Moon, King and Queen Mask - Raven Servellon

The Gloaming Mirror

-Bianca Rose Ambrosino

After a short night, before

the full sun

I stood, bleary

in front of a long,

dark mirror

I did not turn the light on

(not yet, not myself)

I focused & unfocused

on my face, & it changed

It changed into a stiff

covered book, bound &

standing on its spine &

edge

slightly open so that

the gilded

edges of every

page spread apart

just slightly enough

to become

600 slices of faces

& nameless,

in awe

I was every mother & son

& enemy of all

the trickling of my blood,

converging in waves of discretion

into an ocean of my one, hideously

intricate, ever shifting face

holding in all of the monsters of the sea

from bursting into the air (meant for doves)

And out of the dark, in the long gloaming mirror,

so rose the sun as the window behind me, cast

before me, lured my gaze into the growing light

& at once I was seeing my seeing & I

shut

Losing Time - Bianca Rose Ambrosino

I want to

dig my toes into

the sands of the hour

g l a s s

of years

w a t c h

the grains flow a second

time, upwards

c l i m b

a rope and become

the pendulum

back & forth

&

back

in a sandstorm

recount

recall

remember

remind

winding

clocks & clocking

&

filling

the glass

with water to turn

the glass of hours into

a shapely

snow globe

& shake & remember & know

I a m s n o w i n g

•°*:;°•`*:;.`°•

To Visit Who You Lost - Bianca Rose Ambrosino

The music of the rain

drifts around the covered porch

A song, symphonic movement that booms

with heartbeats in

rocking chairs next to empty rocking horses

As thunder

and licks of lightning beyond the screen of the wet door

and the chimes in the wind

and the death in the window all

howl You are here Under the weather

that’s shielding the dark from the Moon

until the flood floats you

up

to it

To visit who you lost in the music of the rain

in rocking next to empty rocking horses

in not looking at what’s right there

in looking at what’s left you

You are here

shielding

the dark

you feel the flood of

light that

the Moon rose

before you

the rocking horse

floats

back up to me

upon the Moon

The music of the rain

drifts

The Magpie

-Hazel McCorriston

The steam from the kettle lands in a cloud on the window, which overlooks the flat

rooftops of the surrounding homes. Behind the light mist a magpie hops along the

slate tiles. I wave my hand at him as he passes. The condensation begins to clear and

his body is larger now from up close. He has a black long object clasped in his beak.

The end of it catches underneath his feet when he moves and he spans his wings to

balance.

He stops a few bounces along, considers his next move. Twists his head

abruptly in my direction and I wonder if he is truly looking at me. I see now that the

item in his beak is a pencil, the paint along its stem peck-chipped, the wood beneath

damp and rotten. It is in fact my pencil, the same dark blue with a red rubber

clamped to its end. We are still and hold gaze through the glass. He drops his new

item onto the slate then, in the rooftop corner where the chimney breaks upwards. I

see there is a twig collection forming where he stands. My pencil is furniture for this

kind of home.

He puts his beak to the tile and begins rearranging the pencil among the twigs,

but it is somewhat larger than the others in his collection and he is frustrated that it

does not fit. Then the long shadowed sun moves just millimetres around the corner

of the building and November copper flows over the magpie’s pencil home. He looks

up, looks at me. He has stopped rearranging the wood, is he satisfied? With a sharp

movement he flicks his beak against the pencil and it rolls down the light slope of the

roof. I fear too that my pencil too does not fit in my hand and its lead will blunt and

smudge my pages. It rolls to the gutter and then he is gone. The pencil is no comfort

to him, my words are no comfort to me. The kettle is boiled. Like him I doubt that my

pencil can make my world better. Water goes into cup and soaks the teabag through,

light to dark and heavy.

The kettle goes back on its base, and then, there he is again, bouncing in gold

afternoon. He hops down to the gutter where the pencil is discarded and rotten.

There, the chance for words, there the astonishing warmth in the makeshift nest he

makes from sticks, unsure if he wants them, unsure if the world offers better.

The next morning is deep and fresh-cold in its darkness, and above me I hear

the bounce of small three-clawed feet on slate. Somewhere between my wake and

sleep is the magpie’s pencil, its eraser intact and its unwieldy shape awkward in a

nest. And my pages, a gulf of thought, void of things that are my own. I had wanted

my words to be like a song, a brief interlude in someone’s mind that tells a life in

three or four minutes. How can new exist if all note orders have been claimed.

But there is the rattle of clawed feet above my head in early morning. He has

something new in his beak now, a flash of myself, a spark of my face red from cold

and tired and firmly in his clasp. Fragment of mirror, of me. Quiet in the glassy

rooftop cold, he is sorrow and joy and I am inside and out, behind my window and in

his voice. I understand from feeling his breath that words shall move me like tide

above sand, rocking, indenting, drawing in and out, and I will not resist his pull. Leap

and rattle, magpie, make my words sing and let my story be the frame of the window

through which I see and speak the world. What is that if not song.

Kid Christmas

-Roberto Ontiveros

Kid Christmas, this dime store desperado who stands outside Enero’s Arrangements like it’s his

job to be a festive gargoyle, blew my mind by walking into the shop and instead of just asking to

use the bathroom actually putting down three bucks for a single rose.

I thanked him for his purchase and as I looked around for a bottle of water to give him,

Kid shook his head and asked me if I would deliver the bloom to a woman who worked just ten

easy traffic minutes away.

We don’t deliver anything under twenty bucks; that is the closest thing we have to a store

policy here, but it was about to be noon and Enero, who makes all the arrangements in the back

and hired me specifically so he could stay in the back when someone like Kid Christmas came

in, would send me out to pick up some take out in like ten minutes anyway, so: “Yes, I’ll drive

your flower out, man. Where to and whom to?”

Kid’s face froze up in cryptic apology and he said: “Here’s the thing, Boss, I don’t know

her name, just where she works – a law office, I think, or could be a stationary store. Here is the

address.”

I held the crumpled restaurant receipt he handed me up to study the stiff scrawl of black

ballpoint digits and the word “CLEO.” The address was discernible and not far at all. I sighed

so that he would feel the depleting nature of my favor, then just looked into Kid’s coal-gray eyes

to see if he might bail on the plan. Kid was smiling. This guy, who I had seen every day since I

started working for Enero, was a very dull diamond, but his eyes were mercy magnets and his

smile could crack into an eager charm that motivated the unguarded to give him any pocket

change if the suckers didn’t watch it. I handed the receipt back to him and he folded up the name

and numbers like a fetish that literally seemed to trick away up his sleeve.

“That’s not her name,” Kid Christmas said. “Or, it might be her name but I don’t know. I

call her Cleo because she looks like a Cleo to me, what I think Cleopatra might have looked like.

Like I call you Boss because you look like a Boss to me.”

“You can keep calling me that,” I said and turned the sign on the door to CLOSED.

Enero was working on funeral flowers for his ex-wife’s brother Jerry. My employer was

not on the friendliest terms with his ex-wife or her family and he only found out about the death

because of the daily legacy house emails he gets. No one asked him to put anything together, but

he felt a genuine compulsion. He was not going to drop the arrangement off though, so that

meant me.

“I take this rose to those numbers, and someone will be at the desk to accept?”

“Yeah, for sure, Boss, might even be her. She drives a red car. If you see that red car

you can just leave the rose under a windshield wiper,” he suggested.

“No, I will make sure someone gets it in hand.”

And Kid Christmas – who, no way was under thirty-five – nodded in gratitude and then

turned to look around for impulse items, which, having given me what was surely his last money,

he could no longer afford.

“Enero, I’m off,” I said and heard a swivel chair in the back room moving, as my

employer knew he would have to stand over the register and await my return.

. . .

When I pulled into the strip mall that corresponded to the numbers on the back of Kid’s receipt, I

looked for that red car and found it fast, some not old enough to be vintage looking Volkswagen

Rabbit, a B104 bumper sticker that someone had tried and failed to completely remove.

I sighed like a two-dimensional working stiff about to punch in a timecard in some

Hanna-Barbera hardhat cartoon, and got out to deliver that single rose, wrapped in that basic

emerald delivery paper which any customer spending less than five bucks could expect.

I walked into the comforting scent of jasmine tea and what might have been just sliced up

office birthday cake, the hot wax aroma of candles and a wick blown out emanating.

A woman with straight shoulder-length black hair looked up and smiled her greeting and

I said: “Hey, does the owner of that red Rabbit out there work here?”

“Oh, shoot – that’s mine, did I leave the lights on again?” The woman said and started to

walk around the desk to check. “I do that, I really do and it’s crazy …”

“No, that’s not it, I –” I held the rose before her and said: “This is from a guy named, er

…Chris. I am delivering this one rose to you. No note, just this simple gesture.”

The woman brushed a strand of hair that had fallen over her eyes back and held the rose,

turning the flower in her grip as if to examine it for some kind of spring-release trick, and

repeated the name: “Chris…”

“Look, that might not be his name. And he sure as hell doesn’t know yours,” I said, and

relayed the morning oddness, but declined to offer any deeper info on Kid Christmas but the

basics. “You might know the guy if you see him outside our shop. That’s his spot. He does not

stray from it much and I would bet he lives in those little apartments behind the Lucky Lotto

Food Store. He knows you and where you work. He even had the address written on a receipt

for me. But he doesn’t know your name unless it really is Cleo. He thinks you look like what

the real Cleopatra was supposed to look like.”

The woman smiled and brought the rose over to a pencil holder and set it on a tilt

between a set of Sharpies and a pink vape pen. “No. I am not Cleo. My name is Miranda. And I

never got Cleopatra before – I always get these two dark-haired comedians that really look

nothing alike but sound like me for sure. I gave this guy, this …”

“Christmas. Kid Christmas, that’s what he goes by.”

“I gave this Kid Christmas this address when he insisted on paying me back,” Miranda

said and shook her head and tried to figure everything out.

“I am guessing you gave him more than a few bucks, maybe more money than he was

used to getting or maybe he wanted to thank you, or he was charmed into mustering up a token

of gratitude. But really, you know he’s crazy, right? He goes by Christmas because he used to

wear these holiday lights around his chest, over his T-shirt and plugged into a battery pack in his

jacket. The guy always wears a jacket. No lights today when he put down for this rose but, yeah,

a jacket.”

The receptionist smiled. “I remember. Yes, I did help him out. Jesus. Almost six

months ago. Yes, by your shop, that sushi place where the whole office was having a kind of

end of the year party. He was outside and yes he had the lights on, and after I complimented his

costume, all those lights on a jacket I thought was a costume and then gave him a Target gift card

that was like a door prize, and a twenty. He insisted, really insisted, that he wanted to pay me

back because I looked like someone he said.”

“Cleopatra – or what people say she is supposed to look like,” I said.

“Well, he couldn’t think of who just then.”

“He was thinking of an actress,” I said. “Some black hair and bangs beauty, no doubt.”

Miranda blushed. “Like you said, he’s crazy.”

. . .

When I came back to the shop, the sign was turned back to OPEN, and Enero was in the front

and already done with a simple arrangement of Birds of Paradise in a teal vase.

I placed a sack of tacos I picked up for him by the register and nodded at his work.

Since I already ate in the car and knew I would be heading out to deliver this arrangement

in no time I asked my boss if he needed a soda from the next door store.

Enero shook his head and then informed me that I didn’t have to drive this arrangement

out for him. He’d changed his mind. He wanted to pay his respects, and say goodbye to his

dead ex-brother-in-law. He would go early. “The viewing is at five but they always let the

flowers in. If I go now I can say goodbye to Jerry and be out before I have to say hello to anyone

else. Which means you have to watch the store until five.”

He said all this with a straight face, but even as he spoke out his scheme to skip the

service I knew there was no way he would not just stay for the full funeral.

Five minutes after my boss left I turned over the little cardboard store sign back to

CLOSED to let the sidewalk world know we were done for the day.

Gnosieness - Raven Servellon

Strange bird

-Priya Parikh

I cock my sleepy head east, then northwest, craning my neck and crinkling my brows. A conscious step

toward a strange croaking spilling over the branches. A neon flash, gone almost as soon as it registers.

They have yellow beaks, if I remember correctly. There it is.

Is it?

It is.

It must be.

Is it?

It is.

Or maybe it was just another belly of another leaf winking at me?

Dare I say - I saw the toucan that day? A bird as strange as me, so far away from home, its rain-kissed

eyes just as curious and cautious and finding mine. The minute lassoed by stillness, careful enough not to

startle it, I remaining careless enough to just see it scuttle.

Another morning with the moon on a stroll I’d been choreographing for days. Banal and beautiful and

ripe for the pricking. And when something I remember flies into vivid color, like a vulture ruptures the

placid Lagoa, I can’t help but look and wait, keeping the yearning docked. Bewildered but here, sifted

into the very second, a powder ready to be blown away. And then clumped by the succulence, glued to the

ground just to hope to be trampled on, to flatten, to dry.

Storybooks and sanctuaries have serigraphed the toucan in my sleepy head. There is no confusing the

toucan for another man — animal.

bird.

Bird.

Familiar in the way a dream might be, far enough to taste the water at the end of long roads dipping into

sunsets, dying the closer you get, delayed for what seems like an eternity, only to be stretching alongside

you the entire walk home.The Lagoa reads like hot milk, and if I remember correctly, toucans feed on

berries that would end up curdling the whole bowl. A visitor that lends his yellow for my lips to fall apart

at the cusp of the canopies.

But my sleepy head yawns instead - the sky, the sidewalk cradling it centered. Lullabies from the distant

sea, the parakeets’ mantras, and the snare of my gait roll into symphony again.

The toucan may have seen me that day. Native and free, fleeting by nature, us two strange birds. Let’s not

deny each other the pleasures of a voyeurism so spotless and naïve.

Not quite a not quite, barely a maybe, and none of the sizes between a not yet or an almost seem to fit

either. Perhaps a similitude of certainty and the shoulder turned away from a nothing. A satisfaction of a

something only awakened by the mourning.

And my sleepy head still knows dreams from waking life.

And a croak from a chirp.

And to think back and back to that day.

It’s a toucan, I’m sure of it.

It is, isn’t it?

Is it?

It is.

-

To P. - Gabriella Garofalo

Then what?

The dark swallows wandering highways,

Speed the only option for haggard souls

As restless women and new puritans fight back,

Fed up with tangles of twigs, dew-laden blades,

And their whispers-

Not them again, please, and no, we can’t bloom,

Breathe, belong to the blue, if stars go blinking by

Like distant thoughts, or skittish waves

Always give in to shores-

So let their limbs dance, soul, you just lie silent

Under ice blue blankets, shun those eyes

Gleaming dews hold to ransom-

Can’t you see the sea’s becoming

A breathing cathedral where salt and solitude

Lean into the madness of unresolved nights,

Where water howls smashed prayers,

As waves don’t ask, don’t care, they just keep coming,

And wolfing down prayers while hope thinks she’s

As infinite as the sky, the poor delusive girl-

End of story, this is a truth she can’t name,

The tales of lost moorings, or uncharted lands

Where under the weight of souls waves

Fall down to blue, and God’s breath bends the tides,

So that faith shan’t be a whisper, but an angry tide

Shouting at your sky, as His hands shape infinity, waves,

And too bad they yield no more than silence, shadows,

A unrequited love, a longing for salt and silence-

You done now? Sorry, but the sky is in conference,

Please try a different blue, maybe the faded denim

Of your jeans, maybe blue veins on your hands,

That map of slow decay.

-

-

To M. - Gabriella Garofalo

Askance, askew, the lovers get no sense

Of a late blue tonight,

As anger shrugs it off, she only cares

About thriving among the grass,

They both shining with a sick dazed green

While sunsets sing of new births,

But heaven’s only hint is a breath drawn

From the field’s scent in those blue nights

Or hectic days when nobody cares

For colours freezing behind the shadow line-

Look, limbs and fields are running wild,

So play it safe, no more cryptic games

With shadows, light, time, infinite,

Cut it out, OK, OK, the soul’s so great

At mocking the dreary life, the daily grind

Of everyday folks, doing the dishes,

Doing the groceries, even falling in love,

Great acting, sure, but what’s the point

If her garden lies north of the rising wind,

Or you can’t give the night a blue leeway

When she haggles with the sky over the stars,

And the angel going astray among mails rife

With “Oh woe is me” or “I’m so fed up”

Sighs why don’t they ever write they feel so fine-

Well, I guess they’re not used to hanging round with light-

Oh, look, how odd, a teen girl at the library

Flashing a micro black top, all cheek and no taste

She shows off her skin like false alabaster,

Sure, dream on, she ’ll never yield to the blue,

That hidden place smashed with shadows,

She knows, if light gets freezed we’ll stay

In the dark, no chance to write-

But what about blue, the sham of uncharted depths?

Well, if souls and God can wait, the grass certainly can’t,

Nor can the stones ready to unfold,

For the lovers’ faults to be forgiven.

A New Beginning

-S.J Sangeetha

The ever-cherishing...

View of the panoramic blue hills

The melodious tone of a Thrush

A glimpse of a distant horizon

The sight of clouds kissing the sky

The Panache of...

Lovers weaving the dream

The demanding depths of a mountain pass

The luxuriant foliage

The sparkly stars in the pitch-black skies

The sharpest gaze at the infinite.

It is a desire...

To descend the hours of hardship

To sightsee a palmy garden

To feel the caressing north wind afar

To recreate the defunct fauna and flora

To sense the aroma of Bethlehem Lily.

Must care...

The emotions swinging in the sky canoe

To mouth shut the gamut of harsh words

To augment the woe of parted love

To fill the voids with the right choice and

To put off rage, a forest fire in action

Exquisite is...

The unheard song from the unknown

The illusion is craving for an Oasis

The reality is time plunging into an hourglass.

Afar, a new beginning undoes

The sunrise, twilight and nightfall, the viewers

Untitled No. 9

-G. W. McClary & Lucien R. Starchild

Maybe we’re at our realest when we’re pretending.

Shy rapped on the office door. Two timid knocks.

“Come on in,” the man inside said. He wasn’t smoking. Shy expected him to be smoking.

“You’re the guy who called, right?” Both he and his office were clean cut and organized, but Shy

didn’t want to close the door.

“Yeah, sorry, I’m kinda nervous. I’ve never done this before.”

“You’re alright, kid. So what do you want to find out?” Shy studied his dark features, the

straight nose, the hair trimmed expertly around the ear, and guessed him to be fortyish.

“Well, we decided it was best if my girlfriend quit her job so she could stay at home and

take care of the house.”

“Uh huh,” he said, not looking at Shy, but sorting through some files.

“So she’s had a lot of time on her hands.”

“And?” Still, he wasn’t looking.

“And it doesn’t add up. Sometimes she’ll tell me about her day, and it doesn’t make

sense, like there are gaps.”

“You think she’s screwing around on you.” Now he decided to look.

“No, I mean, maybe? I don’t know. That’s why I came to you.”

“Well, I might be able to find out a thing or two. I’ll just need some information, and the

payment of course.”

“Yeah, right, of course.” Shy slipped out his wallet and handed off the bills, placing them

flat on the table and sliding them across. “Sorry, I’ve always wanted to do that.”

“Right. Let’s get started,” the P.I. said, finally cracking a smile.

Maybe we’re at our realest when we’re pretending—

When the roles we play hold more truth than our names,

When the lines we speak in borrowed voices

Carry the weight of all our unspoken pains.

The lover in the script kisses with a fire

That the timid heart refuses to show.

The hero in the tale stands tall in the fray

While the real one trembles, afraid to let go.

So let’s raise the curtain, let the scene unfold—

Truth is a shadow that follows the light.

Maybe we’re never more honest than when

We pretend we’ll be okay tonight.

Shy waited until after dinner. Beth was in the kitchen scrubbing dishes when he laid the

photos on the counter beside her. They were grainy shots of her coming and going from a

building downtown, one that rented out spaces to various kinds of artists.

“Why did you hide this from me?”

“I didn’t want you to think I was squandering my role as housewife,” Beth said, drying

her hands. Shy imagined something beautiful being produced by those spindly fingers.

“Baby, isn’t that why we agreed to this, for you to have more freedom?”

“Yeah, but I’ve been… I’m scared to say it.”

“Beth, what is it?”

“That’s where some of my money has been going.”

“How much? No, wait, it doesn’t matter. Honey, that’s fine. I gave you that money for

you to spend it as you please. I’m just shocked and honestly a bit hurt that you felt like you had

to hide this from me.”

“What I was doing, what I’m going to keep doing, is sacred, and you should have thought

about that before you violated my trust like this.”

“Should I be asking myself why you wouldn’t show me your sacred?”

“Have you shown me yours?”

“What?”

“Do I need to go behind your back and hire a private investigator to find out your sacred

place?”

“You know my sacred place is with you.”

“You say that, but it’s too easy, too simple. You can’t find the sacred in other people. It

comes from within.”

“That’s where you’re wrong. I know you’ve been hurt in the past, but I’m not them.”

“You think throwing my trauma in my face is going to get me to open up? Why do you

think I hid this from you?” Shock left Shy’s face hanging in slack-jawed limbo for a few

moments.

“That’s what this is about?”

“I really have to spell everything out, don’t I?” She stormed to their bedroom, slammed

the door, clicked the lock. Another night on the couch, Shy thought to himself.

Beth iced him out for a few days, ignoring him and staring blankly at her phone. He

would stand in the doorway as she wallowed in bed.

“Beth,” he would say, then after a few moments, “Okay,” and he would walk away. On

the third day, when Shy thought the tension would drive him mad, she finally relented.

“Why didn’t you just talk to me?” she asked him.

“Because I didn’t want you to feel accused.”

“You literally hired someone to follow me. Isn’t it a little late for that?”

“I know it looks bad.”

“It looks bad because it is. Well, you found out my little secret, now what?”

“Look, all this talk about that you’re painting, and not enough about what you’re

painting.”

“You really want to know?”

“Of course I want to know! If it’s not too late for that?”

“Ugh, you’re so insecure,” she joked, but not really, slapping his arm. “You gotta toughen

up with me. I’ve got dimensions.”

“I see that.”

“You’re really awful, you know that?”

“Aww, babe, I’m gonna cry. Now take me to your super secret artist hideout. What, too

soon?”

Beth had dabbled in high school but decided to pick it up again. She’d been painting for

months when Shy found out, when the man he’d hired laid out the proof of her second life. She

drove them to her downtown studio, clandestine, until that very moment.

“Come on, you’ll like this part. I have to put in a code.” She keyed in the four-digit

password and the door unlocked with a hiss and a clink. They entered the lobby, passed the

restaurant on the ground floor, and moved to the elevators.

“These things can be a little crotchety. You’ll see.” She jabbed the ‘up’ button with her

thumb, waking its tallow glow, warm and buttery under the scrutiny of the fluorescent lights.

Ding. The elevator doors opened with a wheeze.

“After you, mon frere,” Beth said, following him in.

“Beth, look,” Shy said, pointing at the control panel, a waver of fear in his voice. Several

of the buttons were lit up, spread seemingly at random across the thirty-two floors.

“I told you they were crotchety.”

They waited as the elevator lurched from floor to floor, until it finally reached their

destination, the third. Beth hopped giddily into the hallway. The stained red carpet was

struggling to keep its grip. The walls and ceilings were littered with holes, jagged with fractured

drywall. Down the hall to their left was a junk-piled storage room, which in the darkness looked

ghost-ridden and dangerous.

“How do I know you’re not taking me here to kill me?”

“Why do people always joke when they’re about to be murdered?” She fished her keys

out of her purse. “One sec, just gotta unlock my death chamber…”

It was a small room, padded with noise suppression cushions, so it must have been a

recording studio, complete with a derelict vocal booth. The mess of wires and cables dangling

from an abscess in the ceiling said that room hadn’t been live in a long while. In a corner, by the

window which looked out on the street, an incomplete painting rested, half-naked, half-revealed,

on an easel. It showed a valley surrounded by mountains, and all throughout the valley were

these little towers made of stone. At the foot of the mountains, there was the start of a small

pond.

“How many of these do you have?”

“A few.” There were easily a dozen leaning against the walls.

Shy studied the other paintings. They were all fantastical landscapes like the one on the

easel. The dividing line was always at a different angle, but she left roughly half the canvas blank

every time. The border of the completed portion wasn’t even or clearly defined. It was textured

to match the brush strokes of whatever object the edge fell upon. It was an invitation, not just to

complete her vision, but to mirror the way she painted. Shy got it right away. He thought of all

the times she’d been left behind by family members and lovers, how she’d been reduced to

storing up and concealing herself, forced to put up walls in order to survive. Those paintings

were her escape. Shy felt a pang of shame as he realized she was escaping from him.

“Wouldn’t it be crazy if whoever first looked at one of my paintings got sucked into

them, and they couldn’t escape until they painted the other half?”

“Yeah, that’d be pretty crazy.” He spun his pointer finger next to his head. “Coo-coo,

coo-coo.”

“Shut up, these are the things I think about when I’m here. I really want people to get

involved in my work.”

“Have you thought of displaying them somewhere?”

“You mean like in a gallery?”

“Of course, eventually, but maybe a coffee shop in the meantime? I know a guy who

makes a living off his paintings that way. Not to compare you with him. He’s one of those people

who are just wayyy too positive, if you get what I mean.”

“I know the type, but you don’t have to put other artists down to make me feel better. I

know I suck.”

“No, I actually really like the concept. It’s interactive art!”

“Stop, you’re just saying that.”

“I’m saying it, and I’ll say it again. I think you’re onto something.”

That night, Beth imagined an interview, flashbulbs strobing, microphones shoved

aggressively in her direction.

“What’s next, half-finished vases? Half-folded origami perhaps?” the reporter asked her.

“I plan to continue painting in my style. If you see me producing work in a different

medium, then you’ll know my focus has shifted.” Her statement was poised, well-rehearsed.

Should I be asking myself why you wouldn’t show me your sacred?

Was the offering too frail in my hands?

Did my fingers tremble, too human, too flawed

To hold what your silence withholds like a demand?

Or did the moon, that night, press too close

Its silver tongue licking the edges of your name?

Did you fear I’d mistake your pulse for prayer

Or mistake my hunger for grace all the same?

I would’ve traced every scar like a scripture,

kissed the wounds where your godhood had bled.

But you kept your divinity locked in the shadows—

So I worshipped the you that you left unsaid.

“Breathe,” he told her as they stood outside the door, both toting boxes of her paintings.

“Think of it as an unofficial art opening.”

“You’re not helping.”

“Sorry, I’ll shut up.” He locked eyes with her and raised his eyebrows as he leaned into

the door, opening it with his back. There were a few customers inside the shop. The marble

countertop offered bagged goodies, all homemade. A long couch lined the wall opposite the

counter, and another smaller one sat before the window. Shy thought of saying, “Your paintings

will be nice and cozy here,” but he held his tongue.

“Hey, guys,” the barista greeted them, her ponytail lassoed by a ball cap.

“Hi, I called about displaying the paintings,” Shy said.

“Let me go get Mark,” the barista said, ponytail just a-bobbing as she went into the back.

Mark was the owner, and the one who agreed to let Beth display her paintings. He was in his

fifties, with maybe a few days’ stubble, a greying surfer hairdo (think an overgrown bowl cut),

and low eyes that glistened with the sheen of vast marijuana consumption.

“You must be Beth. Shiloh’s told me all about you,” Mark said. She looked around for a

place to put down her box. “Oh, right, over here is fine,” he said, helping her lower it onto the

counter. Shy sat his down too. They were both a little tired from carrying them. “Good to see you

again, brother,” Mark said to Shy as they shook hands. “Okay, well, my space is your space. You

can put them up anywhere. Hell, even the bathroom.”

“I’d like to keep my work as far away from the temptation of flushing it down the toilet

as possible,” Beth said.

“I’m sure people will love it. Do you mind if I take a look?” Mark asked.

“Sure,” Beth said. He slid a painting carefully out of the box and studied it for a few

quizzical moments.

“Huh,” he said, before sitting the painting down and retreating to his office slash smoke

den. While Shy and Beth waited, a group of young people came in, all patchwork skirts and hole-

ridden t-shirts.

“Oh no,” Beth whispered.

“Don’t, let’s just… see what they have to say.”

“If anything.”

“Ooh,” a girl in the group lulled, making a sound like a slide whistle as she wandered off

to one of the paintings. “Is the artist gonna like, finish them at some point?” she asked the

barista.

“No, they’re supposed to be like that. That’s the artist right over there if you want to ask

her.” At that moment, Beth wanted to rip her little ponytail right off her head. She went red.

“We’re leaving,” she hissed at Shy through clenched teeth.

“You could be losing a customer,” Shy coaxed, putting a chiding melody to his words.

Beth sighed.

“Fine,” she said, plastering on a smile as the girl approached them.

“Hi, cool paintings,” the girl said, “I just wanted to know why you left them, you know,

how they are.” Shy inhaled as if he was about to reply for her, but Beth beat him to it.

“Oh, I, uh, I wanted the audience to recreate the other half in their imagination.”

“I’ll do you one better. How much for that one over there?”

“Oh, they’re all—” Beth waved her closer and whispered the price in her ear.

“Joyce, give me fifty dollars,” the girl shouted across the coffee shop. Her friend

begrudgingly slipped her the cash. “You’ll be here same time tomorrow?”

“We can be,” Shy butted in. Beth eyed him, her mouth slightly agape, dumbfounded.

“Cool, see you tomorrow. I’ll have a little surprise for ya,” the girl said. She tiptoed over

and plucked the painting off the wall, tucking it safely under her arm. The group got their coffees

and left. “Pleasure doing business with ya,” the girl said as she left.

“See, see,” Shy teased her as a smile spread across Beth’s face.

“See what?”

“I told you, if you’d bolted, you’d have missed out on a customer.”

“Ugh, stop calling her that. How about… patron.”

“Patron it is. Here’s to many more.” They toasted with their styrofoam cups and Beth

thought to herself that she could die happy.

Beth started a bit of a local craze. People loved to take the paintings home and complete

them, then show them to the originator, trying to match her imperfections. Skilled painters were

too precise, raw beginners too clumsy. It took a person of similar skill and experience to really

match the style. Still, it saw paintbrushes in the hands of those who hadn’t touched one in years,

if at all, where it was once a dying art.

The first customer’s, or patron’s rather, completion fascinated Shy the most. By sheer

chance, they must have been painting for a similar amount of time. She matched her brush

strokes perfectly, finishing the painting with a tortoise and a peculiar little tree around the pond.

Its trunk didn’t branch but was rather a continuous stalk that curved in a spiral. At the center of

that spiral, where the stalk terminated to a keen point, there hung a single fruit, which was bright

red and bore a striking resemblance to a human heart.

“You want to hear a confession? Sometimes I use my knuckles, when the paintbrush just

won’t do,” Beth responded after the first patron quizzed her about how she achieved the texture

of the towers.

***

“So, your art inspired me,” Shy said.

“Oh, it did?”

“Turns out it’s even more interactive than you thought. I started writing a story based on

one of your paintings.”

“Which one?” Beth perked up, her heart on a tightrope.

“The one with the fruit shaped like a human heart.”

“Oh…” Beth slumped.

“What?”

“I didn’t paint that.”

“I know, but that’s what’s so cool about your art. Now there’s another artist involved.” He

paused. “Moi.”

“I guess it is pretty cool,” Beth grinned.

“So yeah, do you mind if I get in touch with the… patron who completed it? I’ve picked

your brain, now I want to pick hers. You know, for story ideas. Then I’ll, you know,” he

interlocked his fingers, “Put the two together.”

“Okay, sure, so you can get both sides of the story.”

“Exactly. You get me. I love you.”

“Love you too, Shy Town.”

***

One day, while Shy was at work, Beth received a visit from the P.I.

“May I come in?” he asked her, flashing his credentials.

“Of course, what’s going on?”

“You might want to sit down for this, ma’am.” Beth continued to stand.

“Oh god, is it Shy? What happened?”

“No one’s hurt, ma’am.” He eyed her from across the room. “Yet.”

“Yet?”

“Let me show you some photos.”

Tears raced across her cheeks as she stared, downcast, at the pictures, her hand over her

mouth, her breath labored. Shy and the patron hugging in the park. Shy and the patron stumbling

into her apartment, unable to keep their hands off each other.

“Wait.” She looked down at his business card where it rested on the coffee table. “I

recognize that name. You’re the guy who spied on me. Shy hired you to find out what I was

doing.”

“I know, that’s why I continued to monitor him. He seemed controlling.”

“So you continued to spy on us? Get out. Get out of my house. This is none of your

business.” She scooped up the photos and flung them at the P.I. He reflexively caught one.

“Leave.”

“I just thought I was—”

“Leave.” She was raising her voice now, her chest rising and falling, clutching her phone.

“Okay, I’ll go. I just thought you’d want to know.”

“Don’t say another word.”

The P.I. left and Beth confronted Shy almost as soon as he got home.

“One of my patrons, Shy, really?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Don’t play dumb. The first girl to buy one of my paintings. I know you’ve been with

her. Did you fall in love when she told you about her side? You think I didn’t notice how distant

you became after that?”

“I—”

“Save it. I just wanted to tell you, looking you in your face, so you know that I know.”

Tears welled in her eyes and her bottom lip trembled. “I’m moving out. I’ll have someone come

get my stuff.” She made for the door. “Asshole,” she hissed, before closing her old life behind

her. And for once in her existence, she was the one who walked away.

Beth continued painting. She earned enough to pay her bills and then some. She found

out that Shy and the patron were on again, off again, but he split with her for good after she had

an affair with Mark, the real catalyst of all this if you really think about it. She wasn’t starving

for love, nor was she actively seeking it, when she met a well-spoken preschool teacher on one

of her walks and knew she’d found the person to whom she could indeed show her sacred. He

was a little messy but kind, and he supported her art but never attempted to meddle in it. He let

her art be, and in so doing set her heart free. And no insecure investigation was going to interfere

with her happiness. With peace and stability secured, she dipped her paintbrush, this time into a

victorious blue-green, and set to work.

You want to hear a confession?

Then here’s one: I, too, have knelt at altars

And called it love. I’ve bitten the sacrament

Let the wine stain my teeth like a threat.

I’ve played the priest in our borrowed cathedral

Absolving you with my mouth, not my hands.

But the holiest thing I ever worshipped

was the ruin of you I couldn’t understand.

So yes—I lied when I said I wasn’t hungry.

I lied when I called this longing divine.

The truth? I’d burn every scripture we whispered

To keep one real verse of yours as mine.

-Greg Arius, P.I.

Heart Conquerors - Raven Servellon

Girl House

-Brooklynn Golinvaux

I used to live here, where those narrow slits still flicker themselves lit

struck by the click of a white cream switch.

I used to spit up cherry seeds in the kitchen and stain my teeth red.

Now cherries make my lips swell.

My abdomen vibrates like the beehive I touched so softly when I was a child

Chest, like that hallowed space beneath the staircase, idle and unreachable.

When you tickle my keys tread lightly please,

I am not the creaky floorboard you reach your fingernail under and lift,

out slips a confession, saying it had to be kept somewhere.

I am without doors and sometimes headless now?

Where do they always come from? Tucking themselves in,

my shoulder blade juts mother wing and why

do I keep growing more arms like chimneys clogged, am I bearing?

They’ll sit humming some tune on the couch and leave you

in that un-funny position.

I wear this house like I’m trying to stretch a t-shirt on.

Don’t they know it’s humiliating?

My body is an unlit hallway cooing empty.

They think all we do is wait for a filling.

Body, a sugar crunch cavity yum?

He thinks I eat his advice for dinner.

Why do they always want to watch us swallow it? Show our nude tongues glossed

with some repeated wish wash, he thinks it’s brilliant.

When the dining set hits the ceiling

my body is an imprint speckled pinkish, that time I wanted to play angels, naked in the snow,

my bleeding toes got stuck to the ice again.

Once when I was five, I ran to the top of Kenwood hill,

landed my body in a purple sled and flew.

The knots from my childhood hairdo

swell in my throat forever.

I am awkward —

Taking each arm out a window,

waving like this house might finally be burning itself down.

The Animal - Brooklynn Golinvaux

I found myself resting in the river’s tendency to hush limbs against the shallow ends.

My hair concerned by the slippery weight of waters tug,

golden bits torn and wound along some mossy shoot.

I used to collect fossils in first grade,

printed sea shells and animal bones, the dainty leaves of long forgotten trees

laced the hem of my bedroom floor

like the impenetrable rings of witches.

I found myself without shoes or clothing,

steam escaping my glacial skin,

like some shivering piece of me could vanish.

Coughing feathers, phosphorescent in pink slush.

It stung when my claws came in,

I discovered my skin ribbed and scaly safe guarded with patches of thick un-shimmering strands,

I was rough.

Wanted to run, engulfed in sticky pine, hide, eat everything, rip open, open open…

Something wild growing at the pit of my spine where my pelvis split unbolted

I wanted to breathe underwater and hiss.

I used to sit with my toes tucked in like a pretzel

centered in my fossilized bedroom humming a shield,

silent wish, I’d think-

poisonous butterflies

fluttering kaleidoscope, new life,

mother wolf barking and unhungry,

the red bellied piranha flashing her teeth at the fisherman

Body, gills and swim bladder body, faultless fur, unforgiving fang,

the tear is the gem is the animal is the ripping open

of an old cocoon crackling comfort

where we never quite fit in the first place.

When I was nine, I found a silver caterpillar crawling in circles behind my knee

I placed her high on the branch of a willow tree beside cedar lake.

Some things we will never see again.

Fight Act II - Brooklynn Golinvaux

Alone, in the dark passage

there is that little moment

Where the things that have the properties to glow are lit.

The little jump

baby bee breathe,

fluid and suspended, the great acrobat!

Firefly tumble and swing

like wind, the definitive brush stroke— such a thrill!

We are clapping our hands together

Cupping, clasping, clapping for

As it was As it was As it was As it was

Alone, in the awful room

the light came on and out.

You’d opened the little cup,

the buzz on your sweat sealed palms

but nothing bright escaped you after all.

So the things that glow are without glare,

the aerial hoop, a swirling loom

hangs in the painted theatre sky.

Alone, script-less and obedient in a rectangular brain

a clear string, missing attachment, bodiless, you’ve got no spark

Cold and damp as sinking mud

fresh on this March night. This can’t be what you’d wanted.

Butterfly - Brooklynn Golinvaux

The side mirror a zipping void of white, then January trees

I was straightening my spine,

to fit most vastly in the front seat.

It’s hard to remember if happiness was bear

or a fish then,

whatever queasiness it came with or didn’t

when you’re approaching double digits

Was there life before the chrysalis?

Does she know to miss it,

when she sees her winged reflection in a drop of rain?

No longer a wrinkle in time but cut of pigment of sky,

Now two bodies of the self, are never gathered for one.

Weaving the under over of space and time by my pen

to make another birth false at best

written under the hot tense of metamorphosis:

changes while remaining solid

compressed beautiful with its likeness.

Always a tease and always still a stone,

fawning clay, molding again around the heart.

and that is all.

so we thank it ten thousand times

it is enough to make our hot tears cool

and never tell how we wanted so much more.

Who Are You - Raven Servellon

Beasts - Gianmaria Franchini

He drives up the coast in fits, stopping at abandoned cars to search for gasoline. Before dawn,

as it is now, he usually prepares to dive for abalone, a vague soul surveying the water, sliding on a

wetsuit, and bellowing cries of love to the creatures beneath the sea. But today, before turning onto the

beach, he drives farther than usual. It’s hard to say why, exactly. He would like, more than anything, to

escape the black road hugging the coast from Point Arena to Mendocino, where imploded cabins hide

behind mad fog spells and half-dead trees, and where sea cliffs hover, ready to fall, it seems, at the pull

of a speargun, into the relentless, darkening waves pounding the break.

But he can never find a way out.

Toward the pallid ocean, wind turbines on sea platforms shine in the starlight. The blades are

motionless in the wind.

Up the road, there’s a motel he’s never seen before. The sign flickers on. In the back, a blue

light burns. Later, they’ll probably serve breakfast to lone hunters. But they can’t take lodgers as the

county breeds bandits, vigilantes, violent wanderers. Hosting strangers for the night is unthinkable,

even for a fixed rate, even for the innocent. If he returns for coffee after the dive, he must watch for the

Wilderness, Fish, and Game gang members, who sometimes take fingers from unlicensed foragers, and

entire hands from poachers. Turning his old truck around, hearing the first faint abalone calls, he

thinks about his meagre existence. In his life, everything is a mystery, as if he were creating the world

anew, from the beginning all over again.

At the beach, the sea is shimmering and flat. The hushed waves lap the shore with their rain-stick

caress. An old rowboat he doesn’t use bobs near a crumbling pier. Near dim tide pools, he kisses his

suit, mask, fins, and gloves, and slips them on. As he squares his shoulders to scan the horizon, a cold

saltwater film passes over his eyes. The abalone sing: “We offer our ear-like-shells, our jaw-locked

mouths, our lathering tongues; take our mother-of-pearl, harvest our flesh, and feed your children.”

Dancing lights, like the glint of knives, the mercurial iridescence of tiny fish, appear where the water

darkens. He shrills a gull’s call, a curt battle cry, and walks toward the lights. When the water is

shoulder-deep, he tests the mask, fingers the shell bag, and goes under with lungs full of air, feeling the

tide pool’s edge toward colder, deeper water. Every time he counts to sixty he rises to spot the shore

and track the lights: There they are, oil-slick scales refracting moonlight. When he reaches them, they

disappear. He checks the shore once more and dives down, counting first to ninety, then higher. Near

the bottom, the calls echo, then diminish. Dark, fertile, and familiar, the abalone wait like children at

the foot of a small reef. Their infantile, muted murmurs are sweeter than the purest harmony. His

heart, so rarely moved, floats toward the surface.

For many years, he hasn’t needed a knife for the harvest; the abalone come willingly.

He repeats the dive, each time filling the bag with a few shells, which grow silent on the

journey to the surface. Working through the dawn, he collects several dozen large, healthy specimens,

and names each of them as a shepherd calls a beloved flock to slaughter.

Later, near the truck, he runs waterlogged hands over the rose-colored shells, the rough outer

growths, the living barnacles. They hum in his hands. When he sees Kairi, his daughter, he will tell her

he can feel them breathe, and sense their probing tongues from the outside. Entire worlds are

contained in each shell. Such a pity, it always is, to pry them dead for meat and pearls. The market in

Mendocino takes nothing else as the half-shells are out of fashion, and food and luxury go a long way.

Driving toward Mendocino, he eases onto Elysian Road, turns inland, and passes isolated, improvised

settlements, which, lying under thick tree cover, never see the full light of day. After the deserted

school and blown-out post office, he crests a hill, cuts the engine, and rolls in silence to the house he

knows so well. Wind chimes flutter in the garden. Kairi’s fish kites jump in the breeze. A dog yelps,

greets him, and settles in the truck’s shadow. Everything is as he remembers, except there are two

trucks in the driveway where last week there was one. His ex-wife split after the flood. He was aimless,

could never provide enough, and felt guilty. She resented losing her freedom, couldn’t fill the void, and

felt guilty. When she left, he had little to give except his grandmother’s old house, where she lives with

Kairi now. Perhaps she has one of her hateful surviving cousins over to help with Kairi, or she’s

sleeping with one hunter or another.

Melancholy washes over him, a stinging, pleasing shower of regret.

Soon, the sunrise stalks the treetops. Inside the house, someone turns on a light. He tiptoes

across the driveway and leaves a basket of abalone on the porch. Back in the truck, he waits, then starts

the engine and drives up the hill, to the coast, and south toward the motel. Before arriving, he sleeps in

the truck for a haunted hour, dreaming of cities under the sea, with people chained to the bottom,

anchoring strands of seaweed tall as redwood trees.

At the motel, a graying, wiry woman is serving coffee, thinking aloud, then to herself. “Burned as hell,”

she says while pouring a cup. Her voice seems to surprise her: “If the burner goes this place will blow.”

The sweet smell of propane wafts over the window seat, where he sits, pleased with the small change

he’s made to his routine, and wonders if he should make another go with his ex. No. She hates him half

the time and he isn’t much for forgiveness. Which is to say, he still loves her and Kairi very much. If he

could spend the rest of his days diving for abalone and driving between their house and Mendocino

he’d be alright. But this love presents a fundamental problem in his life, an obstacle to losing himself

like he wants. Nothing keeps him from driving farther north or south, to what remains of San

Francisco or the no-man’s-land past Arcata. Instead, he drives in circles, stays low, and dives once or

twice a week.

He hasn’t tried the coffee but the woman shuffles to his table and offers more. She lingers,

pouts with her wrinkled mouth, and nods toward a pantry behind the counter. It’s obscured by busted

shelves and kitchen supplies from the motel’s former life. Perhaps she needs help reaching something.

He moves to rise from his seat, but she lowers her eyes and says, “No. No.” A moment later, she points

the coffee pitcher, which has never left her hand, toward the pantry, and says, “See something?” Only

shadows and morning light. Turning to face him, she says, “No one there.” It’s not quite a question.

She cradles the pitcher in both hands. He strides over and flips on the light—just an empty pantry.

“Oh,” she says. “The propane came yesterday.” Then, as if to explain, “An extra set of hands would

help.”

The front door opens, and a bell rings. The jingle is absurd, a relic from another time, when a cafe full

of diners didn’t seem like a distant miracle. A man stops in the doorway. He wears a coat emblazoned

with a giant white “W,” the Wilderness, Fish, and Game gang’s emblem. The “W,” as the gang is called,

protects farms and wild food sources with mafia tactics: they force payouts, sell seized animals, and set

vicious examples of whoever runs afoul of their laws, codes of honor opaque as the omertà. He’s seen

crying farmers plead with them for their last remaining animals, and castrated corpses of permit-less

hunters staked to empty cabins. Over many weeks, the birds tear them to shreds.

The man drags his feet to the center of the room. He glares at a table and angles it to face the

window seat. The woman glides over and pours him coffee. He orders eggs and asks, in a hard,

unyielding voice, if they’re fresh. “From my own brood,” she says, “Same as every week.” He neither

speaks nor moves, and she says, “Must keep the pot warm or we’ll turn up in flames.” She scurries to

the kitchen, clangs pots together, and sings while cooking.

After pockets of silence pass between them, the man turns up his nose and says, “You have the

smell of a scavenger.”

“I’m a diver,” he says, his voice shaky.

“And what do you dive for, coins?” The man’s hat covers his face in shadow.

“Abalone,” he says.

“You pry those clams apart but there’s hardly any meat in that business.”

“It’s all permitted.”

“By the book,” he says, with obvious irony.

A short while later, the woman returns with the eggs. Pleased with herself, she slings the plate

onto the man’s table and blinks toward the window seat. Does she mean something? Perhaps she

knows this man or has heard of his reputation from the hunters who strive, without success, to

conduct their business steps ahead of the W, their mortal antagonists. Perhaps he’s in the thrall of this

morning’s dive, and she didn’t blink in his direction at all. In any case, the man could be after a

poaching violation. The W typically punishes only the most reckless divers. An unspoken rule holds

that the sea has natural laws distinct from the land, and out of deference to what they can’t control, the

W leaves most divers alone. He doesn’t have permits, and keeps his yields small to avoid attention.

Yet this man has unsettling determination in his voice. In such cases, he’s learned it’s better to

retreat into a shell of meekness and wait until danger passes, as storms batter the sea surface over a reef

still as heaven.

The woman clears her throat twice, then speaks: “As you are a chief of the Wilderness, Fish,

and Game officials," she says. “I must report a sighting.”

“I’ve seen the bottom feeder,” the chief says, staring at his breakfast.

“Not the bottom feeder,” she says, “A beast.”

“What beast?” the chief says. His voice suddenly booming.

“A monster, they say, eating farm animals all around.” She clears her throat a third time.

“A goat-sucker,” he says, “a chupacabra!” He chuckles, then purs. “Hide your children!”

“Sir, it is your duty to protect my business.”

“Children, not kitchens, are our most precious resource.”

“I feed half the coast from here to Oregon,” the woman insists.

“Hunters, mostly,” he says, smiling, toying with her.

“It lurked in the pool all night," she says, “Couldn’t get a wink in.”

The Chief turns errant thoughts in his head, and slides from the table. “Is it there now?”

“No, there’s something else.”

“Let’s take a look,” he says, “Slopsucker, your presence is required.”

The woman leads them to an animal pen in the back. He smells something like smoking rubber and

rancid geraniums. She swings the pen door open and waits for them to look inside. There, the carcass

of a half-eaten goat lies on a bed of hay. A mangled incision runs along the animal’s underside from the

throat to the tail. On the still face, the white lips recede above black gums, revealing strangely human

teeth.

“Poor Philip,” she giggles. “Not a drop of blood.”

“Goats give meat and milk,” the Chief says, his voice gentle. “To lose one without offering

suitable protection is a serious offense.”

“It was the beast, not me, sniffing, crouching in the pool—cross my heart and hope to die,” she

says, as if explaining what she’ll serve for breakfast tomorrow.

Earlier, the woman seemed half-mad but honest. She’s calmer now, but he wonders if she’s lost

her mind completely. Coyotes do eat farm animals, but the incision looks oddly precise, and a coyote

would strip the meat or drag the carcass out. Hunters sometimes use carcasses to mark their territory.

And yet, why would a hunter take the blood? Perhaps it was a beast as the woman says. Or, after years

of diving alone, he has lost his mind, and it’s starting to show.

He examines the animal while the chief stands behind him. The scent of damp, rotting fur, like

a rodent’s nest, makes him gag. They could bury the carcass, but the smell would draw attention. He

could toss it into the sea, but it could wash up on shore. Before he suggests either option, the woman

looks toward the kitchen and says, “Have to keep the burner on.” After a moment, they look at each

other, at the carcass, and at each other again. “Burn it,” the Chief says, “and forget this horror.” Then,

perfectly reasonable, “We don’t want the beast to return.” The woman agrees as if it were her idea.

The Chief gathers firewood while they dig a fire pit. He asks what the beast looked like. “Hard

to tell,” she says. “Eyesight’s flying with the birds.” Then, after a few shovels of dirt, she stops digging

and says, “Like a small kangaroo with bloodshot eyes and the limbs of a bat.”

When the pyre is ready the woman complains they have no kindling to keep the fire hot. He

has extra gasoline he found this morning, and volunteers to siphon some from his truck to help. When

he returns with it, the Chief says, “The honor is yours,” and hands him a match to light.

Philip the goat burns quickly, and they watch the smoke disappear into the fog.

Back inside, the Chief stares at his plate between surgical bites. A careful animal, he rises slowly, drops

a fistful of coins on the table, and counts them with short nods. Satisfied, he grunts, rises, returns the

table to its original position, and drags his feet to the exit. With a hand on the door, he says, “You

scared her this morning.” Then, “Break the five-pound limit,” he shows his teeth, “or dive with your

permits in disorder,” he pauses again, “I’ll have your balls.”

The bell rings and the woman startles off her feet as if she hadn’t noticed anyone come in.

He watches the chief’s truck head north. It’s the same truck that was in the driveway this morning. I’m

a careless fool, he thinks. Jealousy rouses from deep regions of his viscera, leaving him hot and dazed. It

would feel good to pass saltwater over the chief’s eyes, dazzle him with the abalone lights, and watch

him drive blind into the ocean. “Everything has a price,” he mumbles, and considers how much this

morning’s abalone haul will fetch at the market. Not much more than food and gas for another week.

The woman clears the Chief’s table and continues her obscure duties, polishing rusty

silverware, staring at cupboards, reaching behind shelves, and searching for something she has not yet

found this morning. She seems to have forgotten about the goat, but while she lingers at the counter,

the spark of memory lights her face, and she says, as if she has finally lost patience, “Closing up. Time

to go.”

Every week he spends a few hours with Kairi after diving. He loves taking her to his diving site, and

cherishes even the abrupt, disconnected conversations with his ex-wife. After leaving the motel, he

returns to the house on Elysian Road to pick up Kairi. As he pulls up, the dog barks, struts to his

truck, and waits for him to climb out of it. The Chief’s truck is nowhere in sight.

“I heard you this morning,” his ex-wife says from the porch. “You don’t scare me, you know.”

She closes the door half-way behind her.

“There’s nothing to fear,” he says through the truck’s window.

“You couldn’t scare a seal pup if you tried. But you’re spooking my boyfriend.” Her eyes drift

to the driveway.

“Are you cavorting with the forest service men again—the gangsters and hunters?”

“So many.” She laughs, though she seems determined not to. The flash of her teeth reminds

him of all the days they spent at the beach together. The roar of the sea muted her laugh then. Today,

her laugh bounces through the trees. She will forget him the moment he leaves.

“The gangster will arrive in a few hours so have her back before then.”

“In one piece, as always.”

“Please, don’t get lost, and don’t wander,” she says. “Kairi, come on.”

She runs out of the door and leaps into his truck. Her backpack has a picture of a whale on it.

On a decrepit picnic table near the beach, he lays out pens and paper he has collected from empty

homes. Kairi draws everything she sees: seagulls, crabs, starfish, otters, sea lions. She draws her dog

hovering over ocean waves with wings and fins. One day last year she returned from the beach with a

backpack full of feathers, sticks, bones. At home, she hung them up and traced their outlines on the

walls.

“Wings and fins, wow,” he says.

“He can go anywhere he wants.”

“Where does he want to go?”

“There are gills too.” She points to fleshy, pink twin blobs.

“You’re good.”

“He wants to dive and chase abalone.” She pronounces the “b” like a “v.”

How wonderful she is, he thinks. The little animal, full of impetuous decisions, uncertainty,

the ignorance and innocence of youth. Every day, she becomes more herself. She has an independent

streak but would be helpless alone.

“Soon, I’ll take you with me.” He says this because he feels that he should, but can foresee he

will never take her diving, and doesn’t want to. He hopes her life will be better than his meager one.

“Let me tell you a story before I have to take you home,” he says, changing the subject. “Do you know

about the turtle that carries the world on its shell?”

“That’s a big turtle.”

“It’s so big we can’t even see it. Let me tell you: Once I was small like you and had a mom and

dad, but I also had a grandfather and grandmother. Things were different in California. There was a

city where we lived, San Francisco, but that city is now under the sea. My grandparents were from

Japan, which doesn’t exist anymore because it’s also under the sea. My grandmother gave me the house

you live in, and told stories she said were very old. She was a good storyteller and would use sounds and

different voices. Her English wasn’t good, but she made the stories fun. The turtle was as big as the

world, which floated on the sea, and it carried the world on its shell. Grandmother would pretend she

was the turtle by craning her head into her body and snapping her teeth. While she was strong enough,

she would take us onto her back and say, ‘You are the world. See? You are floating on the back of the

turtle.’ She would tire and hurt her back but never stop laughing. Then she would fall and we would

crawl over her and die laughing, though we could never understand her completely. Other times she

could be strict and carried around a sadness that I did not see in other people’s grandmothers.”

Driving north, the Chief gives himself a new name. “Angels in heaven hear me,” he yells. “Bless the

land and the people, the fruits of their labor, their hopes and desires.” He traces devious prayers across

his chest, bristling with emotion. “I am reborn: Call me the General.” His mouth stays open after the

sound has left, and his tongue explores the new name, the new calling. He screams: “I curse Chaos, the

enemy, with the voice of my ancestors, and declare vendetta against entropy, the falling, the falling!”

After a bout of silence, he consoles himself: “Someone, no one else, must care to grow the

young. The laws are sacred. Without them, nothing survives.” The wind whistles through the cracked

window. “I must purge the trespassers, starting with the poacher who wants, it seems, to die. Poor

soul, his old woman leads me to her bed. I will raise his daughter as my own.”

The injustice presses so hot in his chest that his eyes burn with pleasure.

After dropping off Kairi, he drives to Mendocino and stares at the brilliant, hypnotic sea for the rest of

the afternoon. Later, at the market, he prepares the abalone for the sale. One by one, he plucks the

shells from buckets of saltwater, cups them in his hands, whispers praise, hisses love, and kisses them

top to bottom. “A worthy price for your children,” says the trader from the entrance of his tent. He's a

short, mysterious man who speaks in familiar tones, as if he was once a diver. After each exchange, he

imagines the trader inhaling the scent of abalone until night falls and the market closes.

The trader plunges his hand into the saltwater and claws out a shell. “Beauty,” he says, “Which

beach?” He tosses it in the air, then back into the bucket. He must know that abalone this size come

only from a few beaches.

“Gualala,” he replies, naming the nearest permitted site.

“Never seen such marvels from Gualala,” says the trader. “This morning?” He lifts the buckets

onto a scale the size of a small statue, and nods at each weighing.

“I dove through the night,” he says, and slips, offering too much information, “And slept

through the morning.”

“That’s funny, I made the morning permit sweep,” the trader says, “Didn’t see you.”

He feels the sale, and perhaps more, slipping away. But, before he volunteers the name of the

beach near the motel where he dove this morning, the trader throws him a lifeline: “Might have missed

you.” Then, “These look good, let’s split them up.” The trader steps into his tent to file paperwork,

perhaps, or to suck the sea slime on his hands.

He begins the dread work. Grateful, after all, that the abalone entrust him with their lives, he

keeps the chain mail glove and stubby knife out of view until the last possible moment. In view of the

foragers, hunters, and traders mingling about the market, he pries half the shells open, digs for pearls,

and slices out the flesh. The shells are pliant in his hands, but their soft, resigned death cries, like the

bleats of clucking hens, nearly make him cry. The other half he leaves for the trader to sell whole.

This week, he will dive once more, and see Kairi a second time. His life will continue on a drab

path until it’s too cold to dive, the abalone die, and the sea swallows the coast forever. But it was a

good dive this morning, and perhaps that is enough. He remembers the woman at the roadhouse, and

wonders how she has stayed alive among the hunters, gang members, and beasts. He finds himself

searching for the chief’s hat and inscrutable face among the faces in the crowds. Just as he thinks he

spots the woman’s white hair, the trader returns with a dark look on his face.

“Your permits,” the trader says, changing tone.

“You’ve never asked about them before,” he says, trying to salvage the situation.

“Look, your hauls are good,” the trader whispers, “but you’re over the limit and without

permits.” He looks over the abalone and asks where they were harvested.

“It’s a secret beach,” he says, not ready to admit to poaching.

“From one diver to another: poaching is a deadly offense.”

“I know,” he says, “I’ve been diving for years.”

“The W is coming down hard on us,” the trader says with a firm, apologetic stare.

Then, as if carried on the back of an inland wind, the General’s god-like voice rises from the

tent behind him.

“HERE is the poacher,” he says, “And torturer of animals.” Indignant, self-serving, his voice

herds attention with the power of music, or a soul-binding spell. “This villain stores poached food

with his family, and burned a farm animal this morning.” A crowd forms in front of the General,

Grand Inquisitor. “The life of his precious child lies on a knife's edge.” He steps aside to reveal Kairi

from behind his great coat. She seems confused more than fearful. “When one of us is in danger, we

are all in danger,” he says. “Can anyone argue with this?” The trader nods. The crowd murmurs

agreement. Some farmers call their animals inside their pens and trailers. Traders put away their wares.

For the first time since the flood, and when his ex-wife left, fear consumes him. His blood

leaves his body, which fights to stay standing.

“What do you say, diver?” says the General.

He gurgles, “They were a gift, for my ex-wife.”

“So you admit to poaching?”

“The goat was already dead,” he says with the conviction of a wounded animal.

“Truth guide us. I have witnesses to the foul deeds.”

The wiry woman’s white hair floats above the crowd as she comes forward. She looks past him,

dazed by the shining sea. “Did this diver instruct you to burn a farm animal?” says the General.

She makes a show of searching her mind and says, finally, “Yes, it was his idea.”

“But the beast killed the goat,” he says.

“What beast?” she says.

“How many children can a dead goat feed?” the General shouts, furious. “And for how long?”

Indignant at the thought of wasted food, someone cries “Justice! Burn him!”

“We have a second witness,” says the General. “Lovely, little Kairi, does your father leave you

abalone?”

“Yes,” she says, proud of her father.

“And where does he dive?”

“Point Arena,” she says and smiles. She has passed the test and looks to her father for praise.

“Point Arena is a prohibited beach,” says the General, his voice mild. “We cannot keep food

sources safe with poachers in our midst.”

“They’re our food sources too,” someone yells.

“Justice hear us, we must not rely on a mere child,” says the General.

The crowd parts and his ex-wife glides through the opening. She’ll save me, he thinks, but is

frightened by her eyes, which hold the uncertain, calculating glance of a woman afraid of public

shame, and, unable to summon the courage to oppose the rabid voices, joins in their savagery.

“The wretch stalks this long-suffering woman daily,” says the General.

She looks at him as one pities a broken toy. She could feign ignorance to cast doubt on the

General’s performance. But, she doesn’t know if that is what he wants. In truth, she has never known

what he has wanted. But with him gone, she can bury her guilt forever.

She drops to her knees, clutches her head in both hands, and cries out in ecstatic pleasure, “Yes!

He comes to watch us! He puts us in danger!”

All eyes turn to him, who is strangely calm. “Cast him out!” the crowd yells.

“The law is the law,” says the General, grave as ever.

“The law is the law,” repeats the crowd, though none know what it might be.

“Take your charge,” the General says. He pushes Kairi forward. “You have until sunset to

escape with your blood. After that, we will hunt you. If you fail to keep her, she becomes our own.”

At the beach, the sun lies below the horizon across an anxious, alien sea. The rowboat is still moored to

the concrete pier. After he rows to the sea platforms, they can hide overnight and continue along the

coast to the ruins of San Francisco. He takes water, a tarp, and food from his truck, and wraps Kairi in

a heavy blanket. “Aren’t you happy we’re together,” he says, hurried, but focused. Her eyes grow wide,

then worried, and she says, “Can’t we dive in the daytime?” “The abalone prefer the dark,” he says, not

convincing even himself. He lifts her into the boat and wraps the blanket tighter. Behind them, not far

up the coast, headlights streak through the falling darkness: The W is on the hunt. He unties the boat,

leaps in, and rows toward the wind turbines, which lie less than a mile from shore. The fog grows

denser, the sea darker—and Kairi becomes quieter.

Halfway to the turbines, he spots a boat with a powerful flood light slip past the shore. It must

be the General. Kairi says she’s cold and whimpers.

Powering through the waves, the General quickly cuts the distance between them in half. His

cries crack through the wind: “Scavenger,” he yells, “Your balls are mine!” When they reach the

turbines, it begins to rain. Kairi cries, first in whimpers, then in sobs, and covers her eyes to escape the

floodlight. But there’s another light in the water, a thousand little candles rising to the surface. He lets

the boat drift toward the platform, watches the lights sparkle, and hears faint abalone calls. This far

out, he’ll have to dive deeper than usual. He sees the General pacing in his boat, and hears his voice tear

through the night: “She belongs to me!” The saltwater film passes over his eyes. “Stay here,” he says to

Kairi, who is motionless in the blanket. For a moment, he’s unsure if he’ll jump. But soon, the dark,

still water drowns out all noise and thought, and the abalone call him to the bottom of the sea.

In each attempt

-Eric Huff

one clue, light behind you. tree fort lungs and a broken cassette tape player. we are dreaming this mellow

baseline, crystal night, crystal river black – shine! driftwood Jesus, your eyes are a glowing ember

remember? hold on, and where were you JC when I dreamed this very bridge, the one lit by little TVs

stashed away in the back of rooms? flash bang Jesus, where were you last standing, cold pressed, with a

dog-end cigarette in your right hand? sing, black river, sing! snag! where are you snake coil? evil

dreamer? as I lean over the edge a bit. nail biter! sinker! when Henry broke – wave maker! how many

dreams does it cost to get on this city bus? how many times do I need to just keep crossing that holy river